Kyungso Park: How did you begin your journey as a musician? Was there a specific point when you knew you wanted to be a musician, or do you feel that you were born a musician?

Peni Candrarini: I was born into a family of traditional musicians. My grandfather is a famous Gender player, and my father is a dalang puppet master. My brother is also a dalang, and my sister a sindhen, traditional singer for gamelan. So we all do music: My brother, my sister, my mother, my father.

KP: What is your earliest musical memory?

PR: My first musical memory is from when I was 4 or 5 years old. My dad was teaching me to sing for the first time. He was singing to me about food (laughs) in a Pelog scale (sings), talking about popcorn and cake from cassava, trying to get me interested in learning the song. I remember clearly that my father would use all the detailed vibrations in the singing, ever since I was 4 or 5 years old. Not just simple singing with flat notes, but the full vibrations of singing, teaching me every detail from the very beginning.

KP: Is music in Indonesia kind of a family job?

PR: Kind of, yes. But only my family in the area are artists. Some of my other family are fishermen, some work on crafts and stone masonry, some are dalang (like Sri Joko). Some are rich, but my family was poor, because life as an artist is hard. But my father still believed that we could get by as traditional artists, because he believed that his kids would be able to have a better life than him. He always tells me, “I believe in your future as an artist.” He never taught me to swim in the ocean, because he didn’t want me to stay by the ocean in East Java like he did, he wanted me to go to central Java to study gamelan. I was born in East Java, which is far from gamelan. He didn’t teach me to swim because he wanted me to go far from the ocean.

KP: Like me, your musical life is based in traditional music, but you also perform very experimental music. Was there a moment when you began to develop more experimental styles?

PR: Yes, there was a specific time. I had been studying and singing traditional music since I was born until I went to high school, when I was about 14 years old. At that time I moved to central Java to study gamelan. I was living near the campus at ISI, the Indonesian Institute of Art Surakarta, but was attending high school at the conservatory Karawitan. At the conservatory, we only studied traditional music, but where I lived near the ISI campus, there was contemporary music and dance. One day I was walking around ISI, and I heard the Sono Seni Ensemble making a recording in the studios. It was the first time I had heard contemporary and experimental music in my life, and I found it so interesting. I waited outside of the studio for an hour, and when someone came out, and I asked, “What kind of music is this?” And he answered, “This is contemporary music, based on traditional music, because we come from all different areas of Indonesia.” They had come together from Madura, East Java, Central Java, Makassar, and they just met and recorded together. I was really interested in this, and asked, “May I come to your rehearsal to just listen and learn more?” And he said, “Yes, please come, every Tuesday or Friday night. But it’s all men – is that ok for you?” I said, “I’ll be ok! I will go!” And I went to listen more.

After that, the group asked if I wanted to go with them to a gamelan festival in Jogjakarta. I said, “Yes, absolutely, I want to see what this performance is like on a stage.” This was a completely new world for me, because until now I had just been singing in the gamelan and wayang puppet traditions. So, I went with them to Jogja. And just five minutes before they went on stage, they asked, “Peni, do you want to do an improvisation with us?” They knew I was a well-known singer in traditional music, so they knew I could sing, but he told me that if I could also improvise, maybe I could join their group. I was very scared, but said yes, I want to, but don’t know how. And he said, “Ok, you’ll go on first. Just follow your heart and play.” I went on stage and made some strange improvisational sounds, then sang in a traditional style, played some flute, and one by one the musicians joined in. And at that time, I felt like I was flying in an ocean of sound, from all different cultures around Indonesia. I knew immediately that I needed this feeling in my life, in my heart. After that, I just prayed they would accept me as a musician. And afterwards, at a group dinner, I heard, “ Friends, how would you feel if Peni joined in this group?” And people said yes! So I joined the group in 2002, doing contemporary and experimental music. And I love it.

KP: It seems you travel a lot, which can be exhausting. For me, moving around when I am on tour, I feel really unstable because I have no house. For some musicians, touring is tiring because you don’t feel you have a home. How do you deal with that?

PR: Actually, traveling makes me happy (laughs). My routine at home as a mother, wife, and lecturer is more strict than here on tour. Traveling is a part of my life. Since I was 15 years old, I toured as a traditional singer to many different places, but what I’m doing now is better. As a traditional musician, I had to do 10 gigs to earn decent money. But in my contemporary music, I just need to do one tour, and then I am able to rest at home. So it’s fine for me, and I enjoy it. The hardest part is (my son) Aruna. But I have a husband and family who support me, who make me strong. I’m a lucky musician. Especially as a woman. Most Javanese women can’t live like me. After marrying and having a baby, they usually stay at home and work only for their husband and kids, oftentimes with no career. But for me, before I married my husband, he knew my way of life. He knew that this is what made me ME, and and he said, “I married you, the way you are; I don’t want you cooking, I want you as Peni, as an artist.” So yeah, I am lucky.

KP: Is it hard to live this lifestyle in your society? Do you get pressure from people about it?

PR: Sometimes. Some older generations will tell me I’m an abnormal woman, that I should stay at home, cook for my husband and kids. Also, at the Indonesia Institute of Art where I work, there are only two other women also working there. Some of my friends get a bit jealous because I travel a lot and have a lot of connections in contemporary arts, not only in music, but also theater and dance. And they tell me I’m doing too much. My boss told me that I had to stay on campus for one year. And when I heard that, I decided I would have to leave the campus, because being an artist is my life. I cannot live without performing. And my family stood with me. But this time, God helped me, because a senior professor told my boss he was making the wrong decision. He thought they should support me, because not a lot of artists can have connections with people abroad. And they invited me to come again to their office, and told me yes, you can still travel. Just bring something back to us from your work abroad. And I said of course — I can help you, and I can really help this campus.

KP: What is the philosophy of your life? What makes you stay happy?

PR: Smiling (laughs). It’s the connection that I make through music — this is what can make you healthy, what develops friendships. That’s why I try to be open with everyone. More connections with people create more open hearts, and that makes me happy. Like even when I feel ill, I don’t want to leave the moment. Because if I leave the moment, that means I’ve lost one of my most important medicines. It was like in OneBeat: I was pregnant at the time. My body was protesting, telling me to rest, to remember I was pregnant! But I really wanted to walk to the studio and record with my group, be with the people. So I did it, walking very slowly of course (laughs).

KP: Do you have one favorite moment or memory from the OneBeat experience, and why?

PR: One favorite memory is when I wrote the composition for Sri Joko, and I told his story to the other fellows in the group. I remember that so well. And the first time we performed that song at Montalvo Arts Center, I saw an eagle, a very huge eagle, in front of me, just when I started singing “Rambu RangKung” – it was unforgettable. It was like a blessing from God. And the heart of my prayer. Because before, I had a dream about Sri Joko. He came to me in my dream and asked me: Please help me to find my way, and use Kinanthi, one of the traditional song forms . So that’s why I wrote Kidung Kinanthi for Sri Joko at OneBeat. And the second memory is during the final show, when I sang that song as the last song of our last show, and it really felt like I was flying. Like Joko was with me and got to hear my prayer in that song.

KP: When I got that news about Sri Joko, I was staying in Copenhagen performing a dance show. This show was about what our souls are doing and where they travel in the 49 days after death. It was quite intense, because there was a lot of energy about human death. And I couldn’t perform the show that night, because it was too emotional. We had to cancel the show. I still remember that day. For me, it’s wonderful to meet you and everyone here at Breve. How has been your experience here?

PR: For me, it’s also great to meet with you both (Elena and Kyungso). I’ve met with Neil many times (laughs). But I heard about you (Kyungso) from Sri Joko – he’d told me about you since 2012. For me, this is a reunion that recharges my memories as a OneBeat Fellow. And it’s so beautiful. Those are perfect memories, to meet with those musicians from around the world. And to remember that on the last day, each fellow touched my stomach one by one, blessing my baby. Very important for my life.

_______

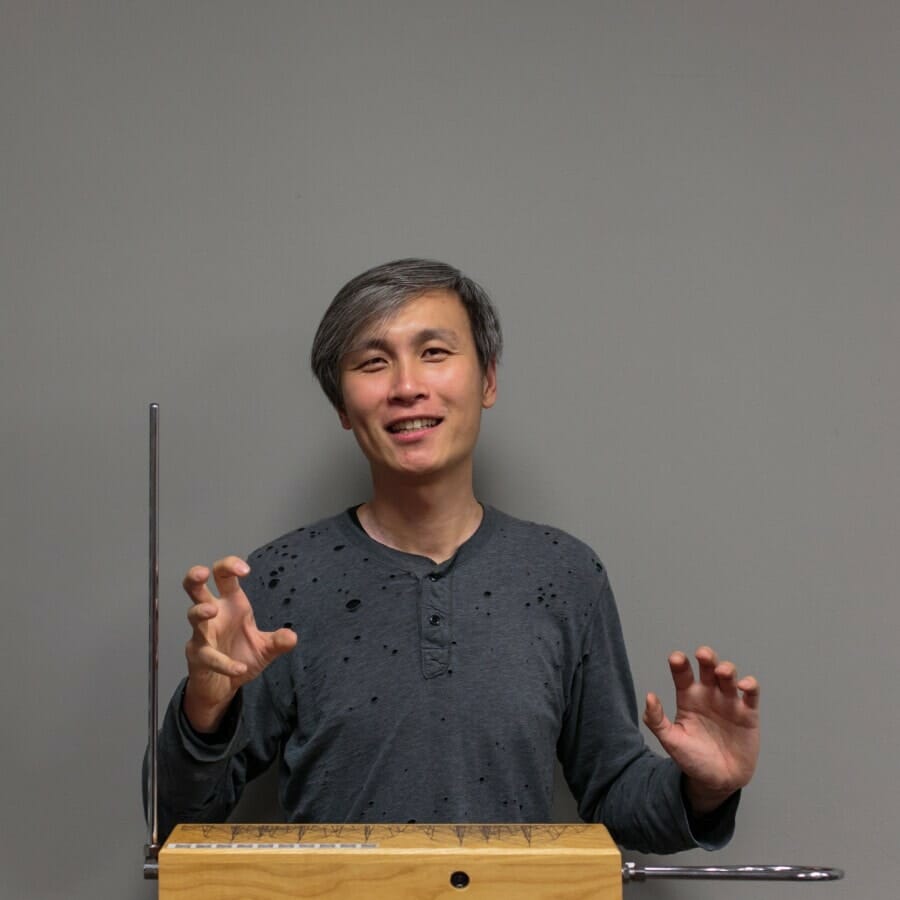

Peni Candrarini is a renowned Surakarta-based composer, educator, and one of few female contemporary vocalists performing in the traditional sindhen style. Kyungso Park is an internationally recognized Seoul-based gayageum player and lecturer. The two spoke this past November at Breve, a musical festival curated by Malyasian musician and OneBeat alumnus Neil Chua, which convened pioneering musicians from East and South East Asia. All of the participants were connected through the international music residency OneBeat. During the interview, Peni speaks about master musician and dalang (puppeteer) Sri Joko Raharjo, a OneBeat 2012 fellow and close friend of Peni’s who tragically passed away in 2014 in a car accident. During her time at OneBeat 2014, Peni composed a piece dedicated to Sri Joko.